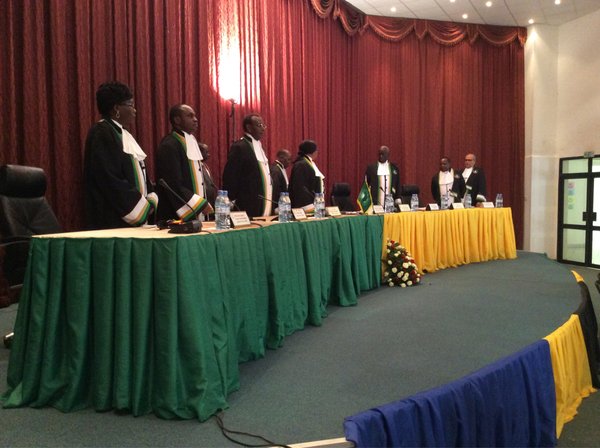

Credit: AfCHPR

On November 20, 2015, the African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights (AfCHPR) issued its judgment in the case of Alex Thomas v. Tanzania, which concerned a complaint brought by a man serving a mandatory minimum thirty-year prison sentence for armed robbery. He alleged that the Tanzanian courts had violated his due process rights by trying him in absentia and by failing to resolve his appeal for more than eight years, during which time his request for legal aid also went unanswered. He also argued that Tanzania did not have jurisdiction to prosecute him for a crime that occurred across the border in Kenya. The African Court held that Tanzania had violated Mr. Thomas’ right to a fair trial, particularly his rights: to legal assistance, to be tried within a reasonable time by an impartial court, and to an appeal, as required under Article 7 of the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights (African Charter). The tribunal also found the denial of due process to violate Article 14(3)(d) of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR). See AfCHPR, Alex Thomas v. Tanzania, App. No. 005/2013, Judgment of 20 November 2015, para. 161. The judgment marks the twenty-fourth application to be finalized by the African Court, which has now decided five of those complaints on the merits. See AfCHPR, Finalised Cases. Watch the African Court’s presentation of the judgment online.

The AfCHPR found no violation of the applicant’s rights to: equality before the law, dignity, freedom from slavery, freedom from torture or degrading treatment, liberty, presumption of innocence, or access to information. See Alex Thomas v. Tanzania, App. No. 005/2013, Judgment of 20 November 2015, para. 161.

The African Court denied Mr. Thomas’ request for release from detention because it found his situation insufficiently compelling, but it did order Tanzania to take all measures necessary to remedy the violations without subjecting him to a retrial. See id. at paras. 157, 158. It ordered Tanzania report back to it within six months regarding measures taken towards these ends. See id. at para. 161.

The Pan African Lawyers’ Union (PALU) represented the applicant, pro bono, at the request of the African Court. See id. at para. 8. Mr. Thomas submitted his application to the AfCHPR in August 2013 and in December 2014, the AfCHPR held a hearing on the preliminary objections, admissibility, and merits of his complaint. See PALU, Alex Thomas Case Summary.

Facts of the Case

The applicant has been a prisoner at Karanga Central Prison since his 1998. He alleged that he was wrongfully convicted and denied a fair trial because he the alleged robbery occurred in Kenya and was thus outside Tanzania’s jurisdiction, the prosecutor failed to prove his guilt beyond a reasonable doubt as demonstrated by variances between the charge sheet and the prosecutor’s evidence, and the State did not provide an attorney to defend him as required. Moreover, Mr. Thomas was tried in absentia because he was hospitalized at the time and he was denied the opportunity to explain his absence. See Alex Thomas v. Tanzania, App. No. 005/2013, Judgment of 20 November 2015.

The High Court of Tanzania rejected his appeal, finding the trial court was correct to convict him based on the prosecutor’s case because the applicant had failed to appear. In order to appeal that decision, Mr. Thomas sought a copy of the court record, which was only provided to him more than four years later and after the Court of Appeal dismissed his appeal as out of time. See id. at paras. 27-31. Similar delays hampered the applicant’s subsequent appeals. When Mr. Thomas submitted his application to the African Court, his request for pro bono counsel and a hearing on his application for review had both been pending for approximately four years without response. See id. at paras. 34-36.

Among other preliminary objections, Tanzania argued that Mr. Thomas’ application should be rejected for failure to exhaust local remedies, including because he did not wait for a decision concerning his request for review and failed to present a Constitutional Petition alleging that the delay in providing him with a hearing violated his constitutional rights. See id. at para. 53. The AfCHPR found that Mr. Thomas had exhausted domestic remedies by appealing to the Court of Appeal – an appeal that included allegations that his constitutional rights had been violated – and that, furthermore, the local remedies were unduly prolonged. See id. at paras. 56-62. Moreover, the AfCHPR found that Mr. Thomas did not have to wait for resolution of his application for review before the Court of Appeal because this was an “extraordinary remedy” and the African Court concurred with the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights, which has stated that only ordinary remedies must be exhausted. See id. at paras. 63-64.

Tanzania argued that Mr. Thomas’ application, presented three years and five months after the State’s acceptance of the African Court’s jurisdiction to decide individual complaints, was untimely. See id. at para. 73. The African Court took into account that the applicant “is a lay, indigent, incarcerated person” and that he had experienced delays in accessing court records and had also attempted to use extraordinary remedies, in finding that his application had been presented within a reasonable time, in compliance with Article 56(5) of the African Charter. See id. at para. 74.

Discussion of Fair Trial Rights

The African Court did not analyze Mr. Thomas’ claim that the Tanzanian courts lacked jurisdiction to prosecute him for a crime that allegedly occurred in Kenya. The AfCHPR did, however, examine his various other due process claims.

In evaluating the fairness of Mr. Thomas’ prosecution in absentia, the AfCHPR relied on the text of the ICCPR, which specifically requires that a defendant be tried in his or her presence, as well as on the jurisprudence of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights in Suárez-Rosero v. Ecuador, the European Court of Human Rights in Colozza v. Italy, and the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights (ACHPR) in Avocats Sans Frontières (on behalf of Gaëtan Bwampamye) v. Burundi to determine that the defendant’s presence is essential to a fair trial. The African Court noted that the judge was aware that the defendant had health issues and that he was unrepresented, thus he owed a particularly high duty to inquire into his whereabouts prior to conducting the trial in his absence. See Alex Thomas v. Tanzania, Judgment of 20 November 2015, paras. 92-99.

In its examination of whether the Tanzanian courts’ resolution of Mr. Thomas’ appeals was unduly delayed, the African Court referred to the ACHPR’s doctrine regarding the “cardinal” importance of an impartial trial within a reasonable amount of time. Similarly, the AfCHPR looked to the jurisprudence of the Inter-American and European human rights bodies, which evaluate the duration of a proceeding in view of the complexity of the issues presented, the procedural conduct of the interested parties, and the conduct of the judiciary. As applied to the present case, the AfCHPR held that the eight years the Court of Appeal failed to accept Mr. Thomas’ appeal constituted an inordinate delay, particularly because his requests for court records went unanswered and his case was not complex. See Alex Thomas v. Tanzania, Judgment of 20 November 2015, paras. 100-10.

Lastly, the African Court found in favor of the applicant with regard to Tanzania’s duty to provide counsel. Although the African Charter does not specifically require States to provide free legal counsel for indigent defendants, the African Court found that it could interpret the Charter to include such a requirement in light of Tanzania’s ratification of the ICCPR, which does provide for free legal counsel, and the serious nature of the charges in Mr. Thomas’ case. See id. at paras. 113-15. The African Court again looked to the doctrine of the African Commission, European Court of Human Rights, and United Nations Human Rights Committee in supporting its analysis and conclusion. See id. at paras. 116-21. Moreover, domestic law required defendants to be provided with legal aid. See id. at para. 122.

With regard to the “manifest errors” allegedly committed in Mr. Thomas’ prosecution, the African Court held that such questions fall within its mandate of ensuring compliance with international human rights standards. See id. at para. 130. While it held that the discrepancies regarding the value of items stolen and other questions were not significant enough to amount to a denial of Mr. Thomas’ right to a fair trial, the AfCHPR did find that the authorities’ failure to ascertain what that property was and who it belonged tainted his trial and appeal. See id. at para. 131.

The African Court rejected a number of Mr. Thomas’ claims. Concerning the alleged denial of equality and equal treatment before the law, the African Court found Mr. Thomas’ claims unsubstantiated. Id. at paras. 138-40. Similarly, the AfCHPR held that the delay in the proceedings did not amount to torture or to cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment. See id. at paras. 141-46. In spite of finding Mr. Thomas’ trial to have been unfair and his appeal unduly prolonged, the AfCHPR did not find his detention to be arbitrary because he “was tried and convicted by a legally constituted Court, which passed a sentence against the Applicant based on domestic law[;] therefore his imprisonment was being carried out pursuant to the court’s order.” Id. at para. 150. Finally, the AfCHPR declined to address the alleged denial of Mr. Thomas’ right to information because it had reviewed the delays in the proceedings in the context of its fair trial analysis. See id. at para. 154.

Jurisprudence on the Right to a Fair Trial in the African System

The African Court has previously decided a case on fair trial grounds in Abdoulaye Nikiema, Ernest Zongo, Blaise Ilboudo & Burkinabe Human and Peoples’ Rights Movement v. Burkina Faso regarding the State’s failure to adequately investigate a crime. See AfCHPR, Abdoulaye Nikiema, Ernest Zongo, Blaise Ilboudo & Burkinabe Human and Peoples’ Rights Movement v. The Republic of Burkina Faso, App. No. 013/2011, Judgment of 28 March 2014. However, this most recent judgment is the first instance in which the African Court has considered whether a criminal defendant was afforded due process. The African Court has previously been asked to review Tanzania’s respect of due process rights, in Peter J. Chacha v. Tanzania; however, it ruled that application inadmissible and made no decision on the merits.

The African Court’s analysis on the fair trial rights, protected by Article 7 of the African Charter, builds on the more robust doctrine of the African Commission. However, while the African Commission has held that there is a duty to grant defendants access to counsel and to free legal counsel in some cases, the African Court’s ruling in the present case is the first to assert a duty to provide free counsel even in the absence of a specific request from an indigent defendant. Cf., e.g., ACommHPR, Interights, ASADHO and Maître O. Disu v. Democratic Republic of the Congo, Communication No. 274/03, 54th Ordinary Session, 28 May 2014; ACommHPR, Abdel Hadi, Ali Radi & Others v Republic of Sudan, Communication No. 368/09, 54th Ordinary Session Session, 4 June 2014; ACommHPR, Egyptian Initiative for Personal Rights and Interights v Arab Republic of Egypt, Communication No. 334/06, 9th Extraordinary Session, 1 March 2011.

Additional Information

The African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights is a regional human rights tribunal. It was established by the Protocol to the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights on the Establishment of the African Court on Human and Peoples Rights (Protocol Establishing the African Court). The African Court decides complaints against States parties to the Protocol Establishing the African Court, brought by the African Commission, intergovernmental organizations, and other States. It may also decide complaints brought by individuals and non-governmental organizations against States that have issued declarations accepting the Court’s jurisdiction with respect to these complainants; Tanzania deposited such a declaration on March 29, 2010.

For more information on the African Court or the African human rights system, visit IJRC’s Online Resource Hub.